A RECORD OF

EUROPEAN ARMOUR AND ARMS

THROUGH SEVEN CENTURIES

by

Sir Guy Francis Laking

CHAPTER I

GENERAL HISTORY OF ARMOUR AND ARMS, PRIOR TO THE

NORMAN

CONQUEST, A.D. 1000-1070

PART 3: LANCES,

SPEARS, AXES, HORSE BITS AND STIRRUPS

Of the lance or spear of the lower order of soldiery I have

already briefly spoken. The long-hafted weapon of the nobility,

in fact the gár of the thegn, for all types of war

spears were known by that name, we can but divide into two classes,

the lance or spear and the javelin. Some finely decorated spear-heads

exist, overlaid with typical Norse designs in silver and copper;

the most elaborate of these with which we are acquainted are to

be seen in the museums of Copenhagen and Bergen. In the British

Museum are a few decorated heads, but less rich in appearance,

as they chiefly rely on con-centric rings of silver and copper

around the haft socket for their adornment.

There are heads of a certain type of hafted weapons found occasionally

in England, though they are believed to be of foreign type, two

of which we illustrate. The use of such spears must have been

exclusively for fighting on foot. They closely resemble in construction

the spetum of the XVth and XVIth centuries, although the lateral

blades or lugs are not so formidably developed, suggesting that

these projections were made rather with the idea of catching the

blow from a sword or axe than for use as auxiliary blades, for

the purpose of wounding. [24]

|

|

|

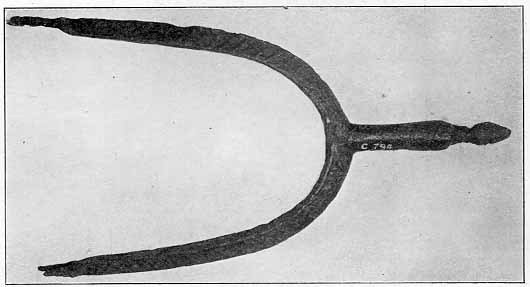

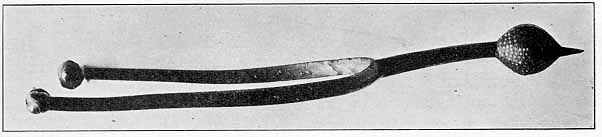

FIG. 29. SPEAR-HEAD

VIIITH-XITH CENTURY

Collection: Dr. Bashford Dean, New York [25] |

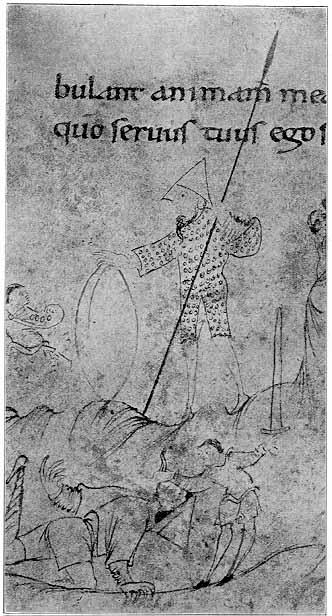

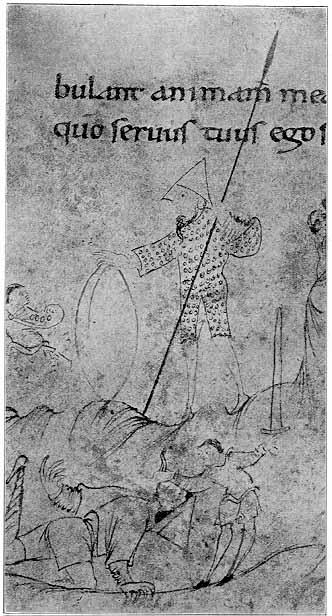

FIG 31. FIGURE OF GOLIATH

He is armed with a spear, the head of which

resembles Nos. 29 and 30.

Harl. MS. 603, f 73. British Museum [25] |

FIG. 30. SPEAR - HEAD

VIIITH-XITH CENTURY

Found in the Thames,

Kew. London Museum [25] |

The two that we illustrate, one from the collection of Dr.

Bashford Dean of New York (Fig. 29), and a simpler, but equally

representative head of the same type, found in the Thames at London,

now in the London Museum (Fig. 30), are representative. We are

aware that this particular type of head with the lateral lugs

at the half socket is assigned to a period anterior to that with

which we now deal, but as an XIth century evidence of their continued

use we reproduce from the Harl. MS. 603, f.73, the figure of Goliath

armed with a spear, the head of which is apparently of this form

(Fig. 31). It is interesting here to note that the oldest relic

of the Romano-Germanic Empire, now preserved in the Imperial Treasury

of Vienna, the lance-head known as that of St. Maurice, or the

holy lance of Nuremberg, containing in the centre of its blade

a nail of the Holy Cross, was originally just such a head as Dr.

Dean's specimen. As it now appears, the centre of the blade has

been cut away to receive the relic. At some period in the reign

of the Emperor Henry IV (1056-1106) the spear-head was broken

in the centre and mended with bands of silver. On these bands

are contemporary inscriptions recording the event. Further restorations

and additions were added to the spear-head under the Emperor Charles

IV (1347-1378). Our certain knowledge of this holy lance commences

with the year A.D. 918, when Widukind, monk of the Abbey of Corbie,

writes in that year it formed a part of the regalia of King Conrad

I of Franconia (A.D 911-918). Its previous history is purely mythical.

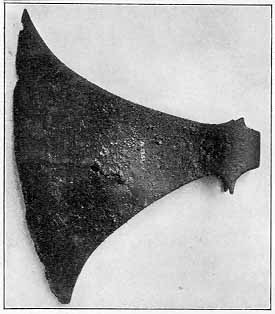

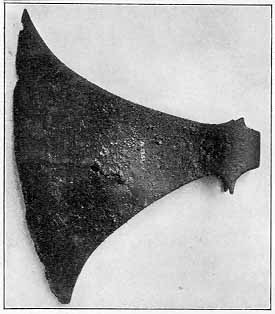

FIG. 32. AXE-HEAD, XTH OR XITH

CENTURY.

Found in the Thames, Hammersmith. London Museum. |

|

The axe, though used as it was by the knightly class of the

old English, has seldom been found in any way enriched, though

perhaps it was occasionally beautified in outline - indeed, of

the many axe-heads discovered it is almost impossible to determine

which are of English and which of Norman or Danish origin. The

axe we may consider as Saxon is shown in our illustration (Fig.

32), a specimen found in the 'I'hames, whilst our illustration

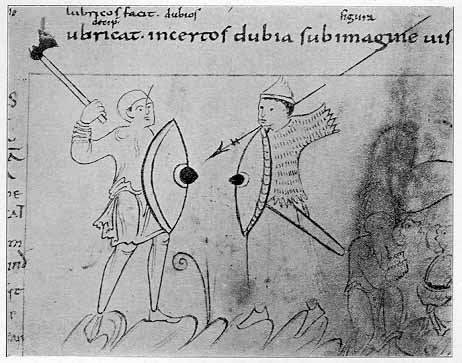

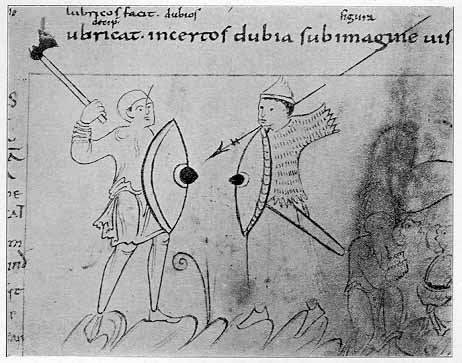

(Fig. 33) shows combatants, aimed with the axe matched against

the spear. [26]

FIG 33. COMBATANTS ARMED WITH AXE

AND SHIELD AND JAVELIN AND SHIELD

Cott. MS. Cleop. C. viii, f. 24. British Museum |

|

It must not be considered that the armaments which we have

described as of old English origin were used in Britain alone;

they represent the weapons of nearly all civilized Europe of the

first quarter of the XIth century; we are likewise reluctantly

forced to admit that the continental countries were ever in advance

of Britain in the adaptation of new types, also that the continental

workmanship shows a slight ascendancy over our [27]

insular production. As an example of this, finds made in

Norway, Sweden, and Denmark show us workmanship of such a high

quality and shapes so advanced that they might readily be considered

to belong to a century later, but by circumstantial evidence they

can be proved to be weapons offensive and defensive of the VIIIth,

IXth, and Xth centuries.

|

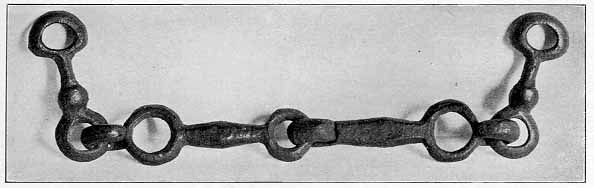

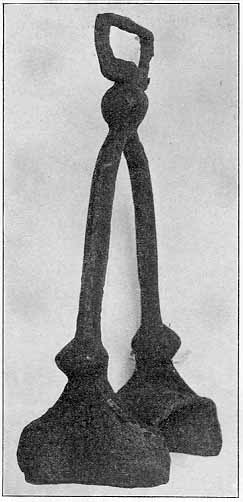

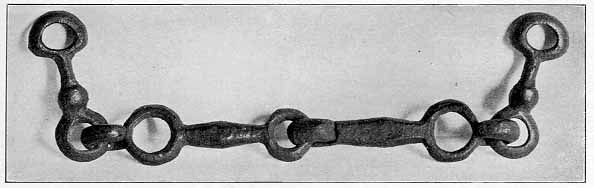

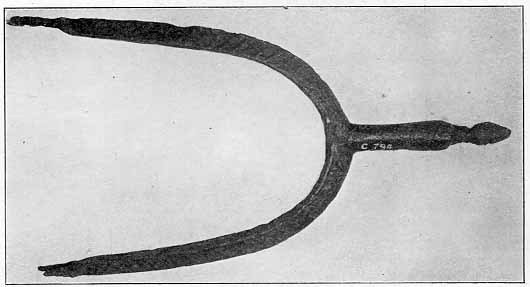

FIG 34. SAXON BRONZE BIT

Found in the Thames at Wandsworth. London Museum [27] |

The horses of the mounted soldiers or thegns were unprotected,

and their trappings of the very simplest construction, though

often rich and sumptuous in appearance. The bridles with which

we are acquainted are merely of the ring snaffle type. An example

fashioned of bronze found in the Thames at Wandsworth is now in

the London Museum (Fig. 34). This specimen belongs to the earlier

Saxon times. [...]

|

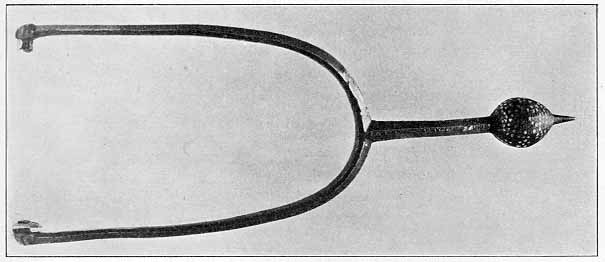

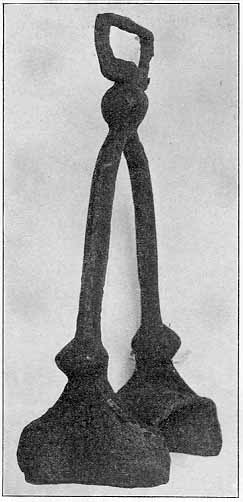

FIG. 35. STIRRUP WITH BRASS ENRICHMENT,

XTH-XIITH CEN'I'URY

Found in Thames. London Museum |

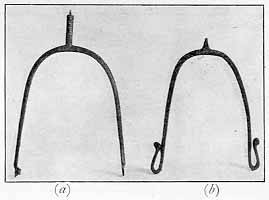

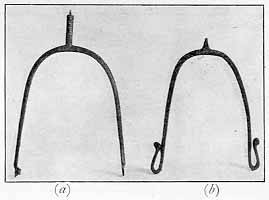

FIG. 36. SPURS, XTH AND XITH

CENTURIES

Found in the Thames. London Museum |

|

[...] The formation of the stirrups,

if not actually of leather thongs, was of the simplest triangular

form, though in general outline they were little at variance with

the shape in use to-day. A fine example now in the London Museum,

decorated with brass inlay, was found in the Thames near the Tower

of London (Fig. 35). The spurs of this period were of the prick

order, the simple heel band and straight goad neck predominating

(Fig. 36 a and b). We give illustrations of an elaborate

pair of spurs that can safely be assigned to the first half of

the XIth century (Fig. 37). They are remarkable examples of their

kind, being highly enriched and in a wonderful state of preservation;

indeed [28] fragments of the leather

attaching straps are still in existence. They are now in the possession

of Mr. H. G. Radford. In all probability they are the spurs referred

to in "The Book of the Ax " by George P. R. Pulman,

on page 567, 1875 edition. Describing the church of St. Andrew,

Chardstock, he goes on to say: "About thirty years ago, on

removing part of the south aisle of the old church, a stone coffin

was discovered in the midst of the outer wall. It contained parts

of the skeleton, but the most interesting relics were the form

of boots upon the bones of the feet and legs, with the spurs still

undecayed. In all probability the remains were those of the founder

of the aisle or the chief contributor to its erection."

|

|

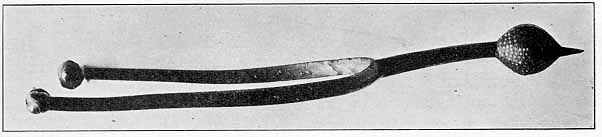

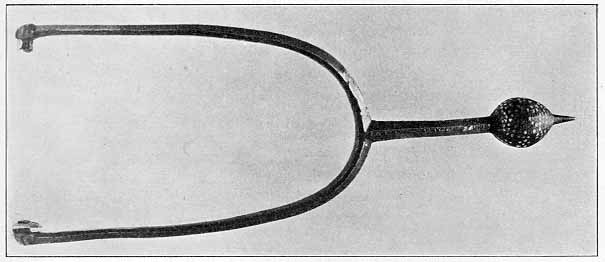

FIG. 37. PAIR OF SPURS ENCRUSTED AND

PLATED WITH GOLD AND SILVER.

First half of the XITH

Century. Collection: H. G. Radford, Esq. |

We may consider these spurs are those referred to by Mr. Pulman,

for they were re-discovered some four years ago in a small, but

old, private collection not far from Lyme Regis, which is no great

distance from Chardstock. [29]

In the London Museum is a single spur of Saxon times, simple

in construction, but enriched with scroll-work in brass and silver

inlay. It was found in the Thames at Westminster (Fig. 38).

|

FIG. 38. SPUR WITH SILVER AND BRASS

ENRICHMENTS

XTH or XITH century. Found in the Thames,

Westminster. London Museum |

With this finishes our very rough account of the military accouterments

of the first half of the IXth century, but so vague is the general

idea of the armaments of the Anglo-Saxon, or, as we call him,

the old Englishman, we can do no better than reproduce one of

the cleverly reconstructed figures, the combined work of M. Viollet-le-Duc

and Colonel le Clerc, preserved in the upper galleries of the

Musée d'Artillerie of Paris, as a very fair illustration

of how such warrior thegns would have appeared when in full fighting

array. (Fig. 39). [30]

|

FIG. 39. PRESUMED APPEARANCE OF AN

ANGLO-SAXON THEGN

From the reconstructed model by M. Viollet-le-Duc and Colonel

le Clerc

in the Musée d' Artillerie of Paris. [31] |

Return to site home page

~ framed ~ unframed