Shamshir: Sabers of Persia, Mughal India and the Arab World

Details from plate XV of Lord Egerton's Indian and Oriental Armour (1896). Above is #757, described as a "shamsher" having a Damascus blade, buffalo horn hilt and gold mounts and its scabbard, described as blue velvet with gold damascened mounts. Below (and reversed in this representation) is #659, attributed to Peshawur, and described as a "shamsher" and noted as having a Khorassan blade and hilt of ivory and gold damascened steel and a scabbard of embossed leather.

Shamshir, which means "curved like the tiger's nail", describes the deeply curved and continuously tapering parabolic saber blade typical of Persia (Iran), Mughal India and the adjoining Arab world from the middle of the 16th century. In this essay, the practice of Haider (1991) will be followed and sabers with blades of this form will be classified as shamshirs, regardless of whether the hilt is of Persian, Indo-Muslim or Arab form; in contrast with the more usually encountered practice of classifying such blades hilted in Indo-Muslim style as talwars. (Haider reserves the term talwar for other curved swords of varying forms generally hilted in Indo-Muslim style, with blades usually wider than a shamshir, often not tapering uniformly and often including a ricasso or unsharpened area adjacent to the hilt, while Pant applies talwar generally to include sabers with an Indo-Muslim hilt such as example #3 below.) Considering that blades of shamshir form, of both Persian and Indian manufacture, were widely traded and interchangeably used with hilts of local manufacture throughout the Near-Eastern Islamic world from shortly after their initial adoption by the Persians until use of the sword declined in the 20th Century, Haider's approach seems justified.

|

|

|

|

Contemporary illustrations most often show these swords being worn within scabbards, suspended horizontally to diagonally and edge down, at the wearer's left side. Though the deeply curved blades are clearly adapted for the draw cut at considerable expense to the potential for thrusting use, these swords are known to have been carried by dismounted as well as mounted warriors. Shamshirs are usually regarded as being optimized for mounted combat at close quarters and such use is supported by period illustrations and writings. Rawson, interestingly, opines that these sabers may well have been adopted more as a hunting weapon for the "elegant slaughter of animals from horseback" than as a combat weapon.

|

|

|

|

These deeply curved blades tend to reach their maximum degree of curvature some 50 to 60% of the blade length from the crossguard. The blade is widest where it joins the hilt, from where it tapers, both in width and in thickness, towards the tip, with the degree of taper being greatest distally. The faces of blades in good condition tend to be flat, but subtly roll (become convex) towards the edge and the spine. The spine will usually be slightly rounded (again convex). Indian blades may show a ricasso (or khajana) which is a length of unsharpened blade at the root adjacent to the tang and a feature far more commonly associated with blades of talwar rather than shamshir form. Shamshir blades are usually formed of wootz or "true Damascus" steel which is considered in detail in another essay.

|

|

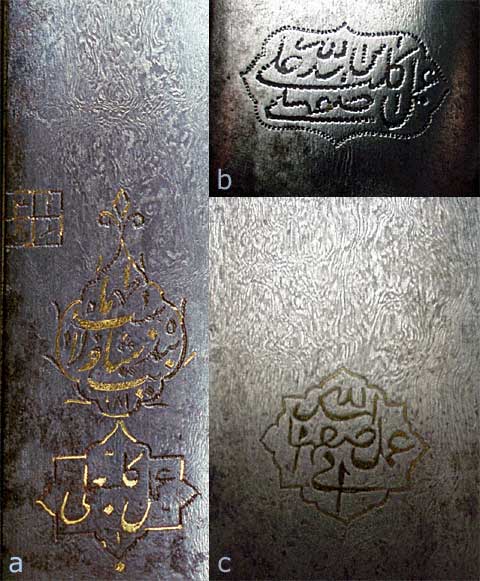

a. is from a dagger blade which has been formed from a cut down shamshir blade. The cartouche forming the lower part of the gold inlaid inscription may be read as amal Kalb Ali and translated to "the work of Kalb 'Ali" while the upper portion of the inscription appears to read 'Abbas bandeh shah i velayat and refers to Shah "'Abbas, servant of the Lord of the World". The inscription is dated 181 or 1181 AH which corresponds to 1767 - 1768 AD, nearly two centuries after the reign of Shah 'Abbas of the Safavid dynasty (1588 - 1629 AD) and the lifetime of Kalb Ali or his father Assadullah of Isfahan. In the upper left is a square, or Bedouh (or: Bedu), with 4 sections, each with a character, which is a characteristic talismanic device. b. is from example 3 below; is executed in a very different manner as a series of very small punches and may be translated as "the work of Kalb 'Ali, son of Assadullah of Isfahan". c. is from example 4 below and is gold inlaid and may be translated as "the work of Assadullah of Isfahan". The assistance of Philip Tom and Rand Milam in translating and interpreting these inscriptions is gratefully acknowledged. |

Shamshir blades will often include one or more of the following inscriptions: the maker's name, the owner's name, a dedication to a ruler, quotations from the Koran and talismanic devices. The most celebrated swordsmith to create shamshirs, Assadullah (or: Asad Allah, Asad Ullah, Asadullah) of Isfahan, worked during the high renaissance of the Safavid Persian Empire in the time of Shah 'Abbas, who reigned between 1588 and 1629 A.D. Essentially no actual details of Assadullah's life are known. Inscriptions proclaiming blades to be his work are common and vary greatly in position of inscription placement, technique and style of execution, wording and calligraphy. Mayer notes inscribed dates associated with Assadullah range from 811 AH to 1808 AD and Elgood reports a wootz blade also inscribed as the work of Assadullah but dated 1921 A.D. - a span of about 500 years! Another famed swordsmith from this same time and place was Assadullah's son Kalb 'Ali (or: Quli Ali) for whom an equally variable and large number of inscriptions have also been documented. From the large numbers of blades so inscribed and from the variations in style, it becomes obvious that these blades cannot be solely the work of the named swordsmith or even of a particular workshop. Considering the variation in the inscribed dates and rulers it seems unlikely that these inscriptions were truly made to deceive contemporary buyers, hence these inscriptions may essentially have been intended as talismanic devices. Exactly which of the blades bearing the signatures of these and other celebrated smiths are actually the work of these smiths is likely now entirely unknowable. Rawson advises assessment of the worthiness of a blade to bear the mark of a great swordsmith, however this does not allow definite attribution of authorship. On the basis of a broad heavy blade bearing a bold, complex wootz pattern, Figel attributed a few of the swords in his collection to Assadullah, as inscribed, however the cataloger of his collection at the time of auction was understandably more cautious.

|

|

|

|

Hilts, while exhibiting a multitude of local variations of form and greatly variable styles of decoration, do retain a core of common features. The quillions (crossguard tips) may exhibit a number of styles: moderate length with rounded button like terminals in the classical Persian style (see #1 and #2 above), stubby and bulbous in Indo-Muslim varieties (as with #3 above) and longer and more drawn out in Arab and Turkish examples (see #4 below). The quillions arise from a centrally thickened and convex crossguard assembly from which integral langets also almost universally arise and extend towards the blade's tip. The langets vary in bulk, often being more delicate on Persian influenced examples and more robust on Indian types. Aside from their obvious assistance in seating the sword in its scabbard, some authors posit a role for the langets as sword catchers or breakers in combat, but such a role seems unlikely for those more delicate hilts crafted of softer metals. A metallic grip is integral to the crossguard assembly in the typical Indo-Muslim hilt, however in the more Persian influenced varieties a symmetric reflection of the langet extends into an inletted area on the grip, which may be formed of two cheeks or blocks of material such as ivory, bone or horn which are riveted into place. Indo-Muslim hilts may rely entirely upon adhesives for attachment to the tang, while in Persian examples the crossguard assembly will be secured by adhesives and the attachment of the grips supplemented by rivets. While tangs may extend the length of the hilt, they are also often shorter. The wire wrapping over the portion of the grip adjacent to the crossguard, seen most frequently on Arab variants, but not entirely lacking in Indian contexts, most likely originated as a reinforcement of an area of the hilt most likely to experience early failure. In swords of classical Persian form, beyond the width of a single hand, the grip turns at roughly a right angle to the axis of the hilt in the direction of the edge. This short extension is covered with a pommel cap, usually decorated in or complementary to the style of the crossguard assembly. The angle and length of this pommel may vary such as with the longer pommel cap arising at a more acute angle on the likely Syrian Arab example (#4 below) or in the form of a bulbous expansion on Turkish examples. In some Indian examples, a knuckle bow will arise from the quillion on the edge side and extend back towards the pommel; a similar function may be served by a chain with Arab styles. The hilt may terminate as a beast's head on more luxurious examples, and such luxurious examples may adopt unique forms beyond the scope of this discussion of the basic characteristics of working grade weapons.

|

|

|

|

|

While the curve of the blade is largely parabolic, the limb of the curve terminating in the hilt is a few inches longer and the blade straightens as the hilt is approached. This asymmetry presents a challenge for the scabbard maker. Persian and Indian scabbard mouths are somewhat wider than their blade; the blades at their widest being 70 to 75% of the inside width dimension of the scabbard mouth. When first inserted, the spine of the blade will glide smoothly along the back edge of the scabbard, however, once the blade is three quarters inserted, the cutting edge will begin to shift toward the opposite side of the scabbard mouth. Turkish scabbards and some Arab scabbards are narrower, employing a slot extending from the spine end of the scabbard mouth for short distance to deal with the asymmetry. Some of these scabbards will even feature a rain guard to cover the otherwise exposed area when the blade is fully inserted. The lining of shamshir scabbards is often of wood and the covering may be of leather, velvet, metal or a combination thereof.

|

|

|

Egerton, Lord of Tatton, A Description of Indian and Oriental Armour (London, W. H. Allen & Co, 1896). (A facsimile edition was published in 1968 by Stackpole Books of Harrisburg, PA). Page 53 and 54 briefly note Assadullah of Isfahan, dedications to Shah 'Abbas and talismanic inscriptions.

Elgood, Robert, The Arms and Armour of Arabia in the 18th - 19th and 20th Centuries (Aldershot, England: Scolar Press, 1994). Swords are considered on pages 10 to 33.

Ferrel, James, The Dr. Leo S. Figiel Collection of Mogul Arms (San Francisco: Butterfield & Butterfield, 1998). The collection is illustrated in color with clear photographs including inscriptions and wootz patterns.

Figel, Leo S., On Damascus Steel (Atlantis, Florida: Atlantis Arts Press, 1991). A discussion of Damascus (wootz) steel well illustrated with numerous items from the author's spectacular collection.

Haider, Syed Zafar, Islamic Arms and Armour of Muslim India (Lahore: Bahadur Publishers, 1991). Pages 162 - 177 contain a convincing schemata for the development of the typical curved swords of the region from earlier straight double-edged forms and an illustrated classification of the basic types of military importance in the Mughal Period.

Mayer, L. A., Islamic Armourers and Their Works (Geneva: Albert Kundig, 1962). Asad Allah is considered on pages 26 - 29 and Kalb 'Ali on pages 46 - 48.

North, Anthony, "Swords of Islam" in Swords and Hilt Weapons (New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989), pages 136 - 147.

Pant, Gayatri Nath, Indian Arms and Armour: Volume II, Swords and Daggers (New Delhi: Army Educational Stores, 1980. The evolution, origins and classification of various types of sword blades and hilts are covered in detail.

Rawson, P. S., The Indian Sword (London: Herbert Jenkins, Ltd., 1968). Rawson uses the term talwar for both sabers of typical Persian form and for those characteristically of Indian form in this excellent monograph which comprehensively covers the multitude of Indian sword forms and their evolution.